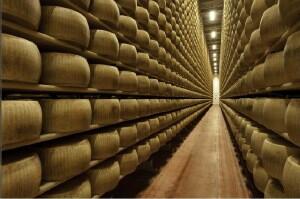

Ripening cheeses at almost zero energy: this is now possible thanks to polyurethane, one of the insulating materials found to be most suitable for this purpose. Good quality ripened cheese is often considered synonymous with tradition and respect for the environment. But do we really know how much energy is "gobbled up" by the industrialised ripening process and how much it costs? In the case, for example, of a warehouse of 35,000 cubic metres, used to store around 4,000 tons of Grana cheese, the cost of energy bills for air conditioning alone amount to around 70 thousand euros per year. And similar amounts are spent on the ripening and curing of other types of cheese, as well as on the ageing of meats and wine and the storage of fruit, and so on.

In this regard, Ersaf (regional body for services to agriculture and forestry), is currently testing an innovative system in Carpaneta (Mantua, Italy): the first cheese-ripening cell for the food industry boasting practically zero energy consumption. The solution is based on a new active thermal insulation technology named Energaid, which has made the industrial process very similar to the traditional one carried out in natural caves. The application has made it possible to reduce certain drawbacks related to the environment, be it the natural one of a cave or the artificial/industrial type, keeping the level of primary energy consumption close to zero, as is the case with a cave. Thanks to this technology, the cost of keeping the above-described warehouse at the correct temperature would be the equivalent of around twice the average Italian family's annual electricity bill (2.7 MWh/year). In the example above, there would be savings not only for the cheese ripener, but also for society as a whole, which would stand to save a further 12,000 euros per year in external costs; in other words, there would be a reduction of costs, generated by environmental pollution, healthcare etc., directly linked to the use of fossil fuels.

The crucial factor for achieving the required performance is the efficiency of the cell/building envelope, which is made from polyurethane panels with special characteristics that make them quite different from those used in passive housing. Obviously, none of this goes against the principles of thermodynamics; most of the thermal energy used in the province of Mantua is of hydrothermal origin. The only machine present for cooling the pilot cell is a circulation pump, therefore there is no drying system. The results obtained will be presented, at the end of the test period, on May 29 in Carpaneta, and compared with the energy and economic costs related to traditional warehouses, and it will be possible to visit the pilot ripening cell.